The walls and spires in question are those that still stand of that old Roman settlement called Eboracum, known at the moment simply, if not necessarily better, as York. While you might be tempted to call this perhaps the old York in contrast to the New York, resist the temptation as it’s leading you astray – the New York was actually New Amsterdam since it started as a Dutch colony, not an English one. That it switched names reflects people and not places – it’s New York because of the Duke of York, not because of the town of York. Here’s proof of walking the walls though and a willing guide for you to come along, too:

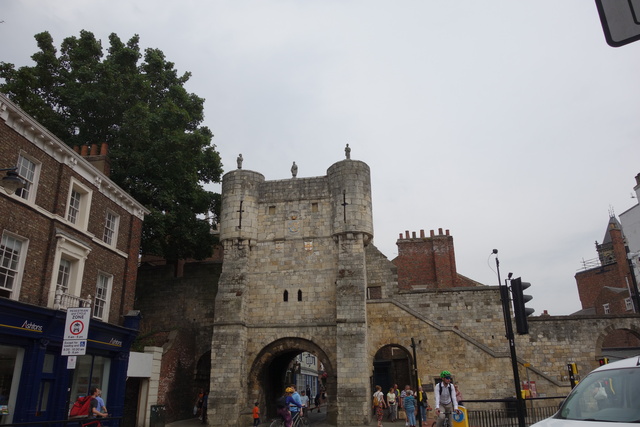

Punctuated with round towers of various designs and a few gates from place to place, these walls of lightly coloured stone still encircle most of the original settlement that was indeed a camp and a fortress right from the start. That start dates back to around 70AD when the Romans picked the place for its strategic advantage at the intersection of two rivers and set up camp to finally calm down the region and claim -or possibly make obvious, if you prefer- their authority over it.

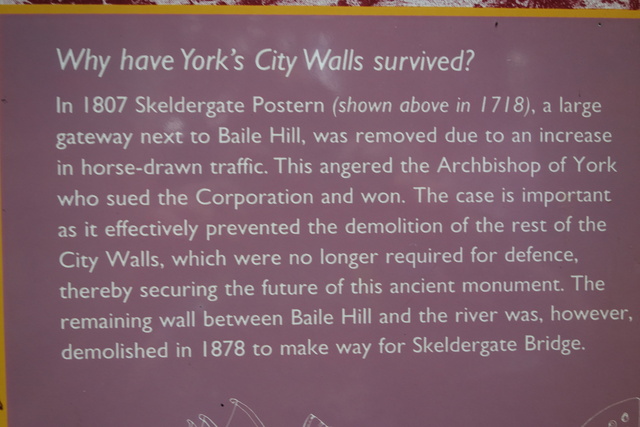

While such authority lasted, the walls stood useful and the town grew and flourished under their protection. Then things changed, of course, as they always do. With time, the once useful walls were found to be increasingly in the way (of horses mainly, in this case) and started to be removed. The authority once claimed with the sword to be held fully and visibly, morphed, fragmented and got increasingly out of sight in a way, too. Still, the battle for the walls happened once more, only it happened in the courtroom this time and it turned the roles around, with the walls facing the town itself as enemy when the Archbishop of York sued the Corporation and won, somewhere around 1800.

What angered the Archbishop was however not the loss of the walls themselves but more importantly his loss of the toll that was paid to him at the gates – only for as long as the gates were still standing, of course. In other words, the walls were defended indeed, for the service they still rendered, nothing else. This reason for the court-battle is not mentioned though at all in any of the “information” signs and leaflets and what-not that abound otherwise. I’m sure there simply wasn’t enough space for it but don’t you get curious as to what else failed to find enough space to be… advertised, properly speaking? Even so, the net result remains that the walls are still standing for the most part while the town found nevertheless ways to expand further without quite obliterating its own past. With time, everything that remained in place still found other uses even if at times not quite fitting perhaps the former glory.

Further afield and on the outskirts of the town, there’s also a round tower looking down from a hill and a rather squat mini-palace of sorts. With the patience or perhaps indifference of stone, they all wait to find perhaps another purpose and be once again brought to life by it. They look quite dignified to me, even if the length of this waiting is starting to show, too.

In the town itself, away from the walls, the stone gets worked upon quite intricately, first by the masons of various ages and then by the winds and rains of all ages. The streets are too narrow for modern cars and as a result, most of the centre is for pedestrians only, making it quite pleasant for walking and taking in all the various quirks of sedimented 1 life and ages.

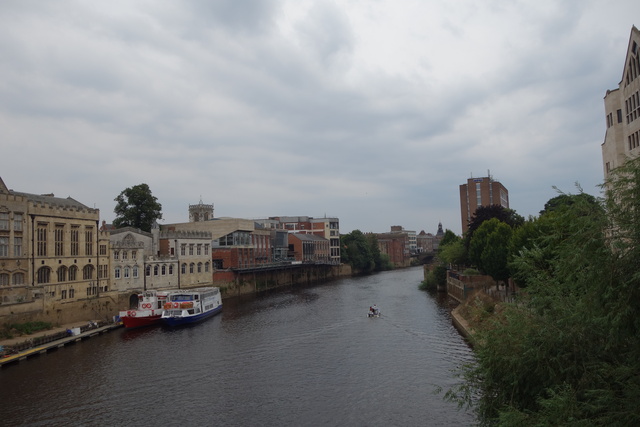

Funnily enough for those in the know, of the two rivers that meet at York, namely the Ouse and the… Foss, guess which one is nicely blue and which one is choked full of ugly green algae? What’s in a name!

The Art Gallery sports a spiky outgrowth as modern counterpoint and contribution to all that carved stone, while a relatively small church lacking the fame of the main cathedral stands elegant and uncrowded on a corner of a street.

The Cathedral that is nevertheless called a Minster 2 towers over the rest and hosts on its side a greenish statue of the emperor Constantine apparently relaxing even if in a rather unlikely pose. He has great sandals though, the sort one sees worn only at fashion shows and never for any practical purpose, in this case what look like flip-flops with lion heads extending on the shins.

In front of the York Minster, the grass truly is always greener on the other side of the fence – only it’s not real grass, of course:

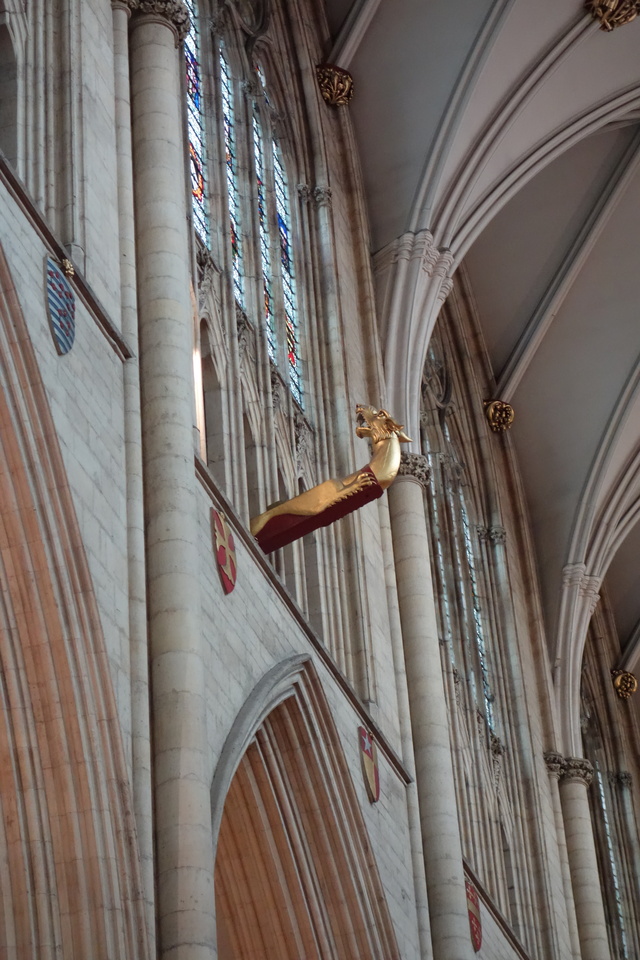

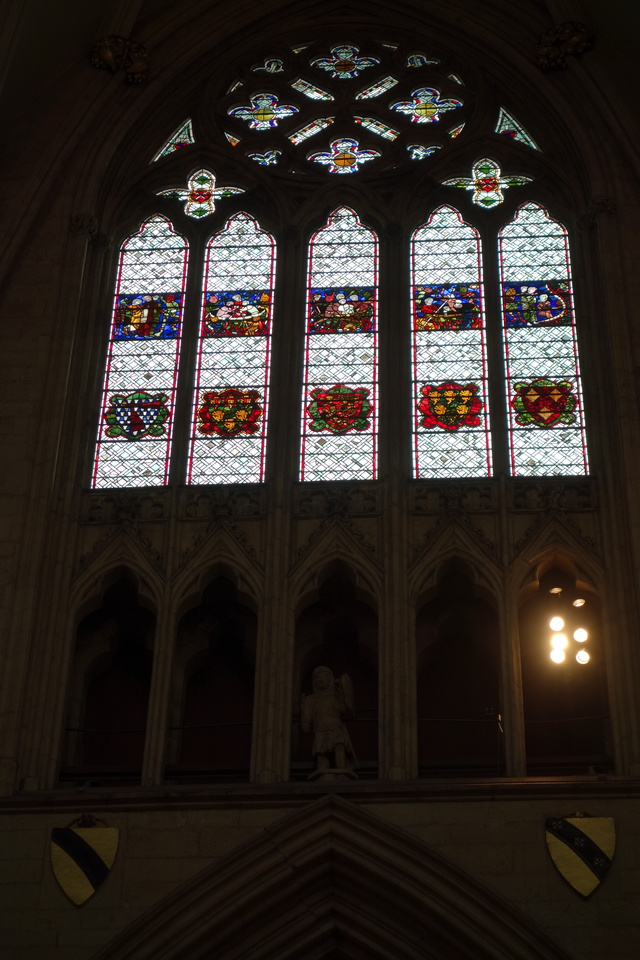

The church itself is quite pretty on the outside and even interesting although not all that homogeneous inside. Apparently its building took long enough for fashions to change even in architecture and as a result, the currently standing construction has for instance gothic windows indeed, but several types of gothic. Which makes the whole approach perhaps not even all that far removed in spirit from the way the houses used to expand in the countryside, too: each couple of years some parts might get added or knocked down depending on new needs or fashions or simply people. Only the York cathedral did it in stone and so it remained long enough for the whole mixture to show as it does. Inside, rows upon rows of carved figures poke out of the walls or attempt to stand neatly in a line while looking nevertheless in all directions – when they have at least heads for such purpose.

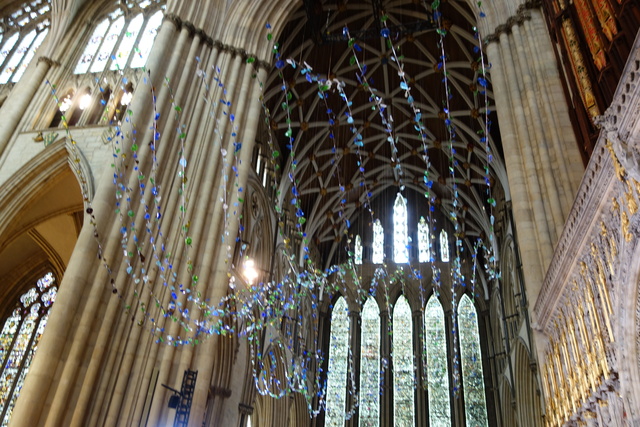

Colourful beads hang from a ceiling at some point for some reason that is entirely unknown to me.

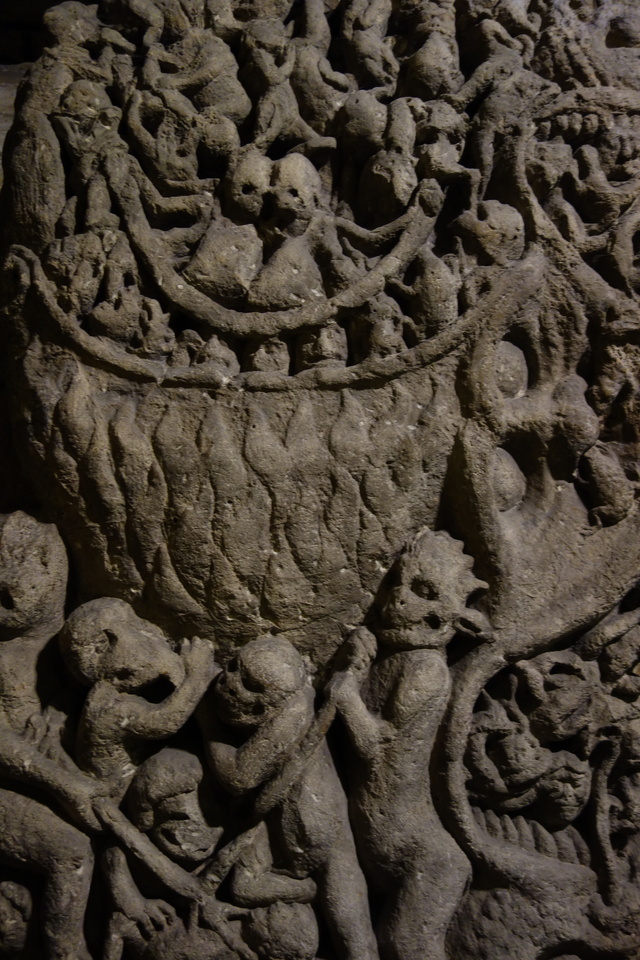

Two knights guard the time on one wall and strike their weapons to mark the passing of each half hour interval. On a different wall, a carving shows apparently some traffic jam at the pedestrian entrance to hell – devils on duty try to shove the incoming traffic faster out of the way.

There’s a crypt inside the church, too, all musty and damp but brightly lit by modern light bulbs. And there’s the cathedral’s spire to scale, quite steep but rewarding, with views from half-away across the church’s front two towers and then, from the very top of the church, across the whole town and beyond.

Trading stone for the metal and masonry for engineering, one can also see in York a rather densely packed history of trains and railways, at the Railway Museum, aptly located right next to the train station currently in use. To compare and contrast though, even after visiting the Mallard and all sorts of Duchesses on rails, we took nevertheless the modern electrical train leaving the town and getting back to the present that is rather than any other present that once was.

- Hrm, apparently English has sediments and sedimentation just fine but somehow sedimented is nevertheless not fine at all. The alternative suggested by native speakers would be assimilated but I don’t think that’s really the same meaning at all: no, it’s not about assimilated quirks or anything else but literally about the sediments of different ages and how they build up as time passes and grinds them more or less together, more or less to pieces, more or less into something else, at times.[↩]

- This is where the church nomenclature gets utterly but also quite typically confusing: normally a church is called a Minster if it has a priest at all times, performing all the relevant duties including visiting parishioners; to be called a Cathedral, a church needs to be the site of a bishop’s throne; since the church in York *is* the site of a bishop’s throne, it should be called a Cathedral *but* the very word “cathedral” is basically too… new to be fully adopted – it came into use only after the Norman Conquest and so York’s cathedral is still called a Minster as it has “always been”. Problem?[↩]

Comments feed: RSS 2.0